What was Arts of the Sengoku Period like?

First of all, The Sengoku period refers to the 50 years from 1573, when Oda Nobunaga(織田信長) expelled Ashikaga Yoshiaki(足利義昭) from Kyoto and destroyed the Muromachi shogunate(室町幕府), to 1615, when the Toyotomi clan was destroyed and the Tokugawa shogunate was established. It is characterized by its very short duration compared to other period divisions.

This period in Japan overlaps with the Momoyama period(桃山時代)culture in terms of art and cultural history.

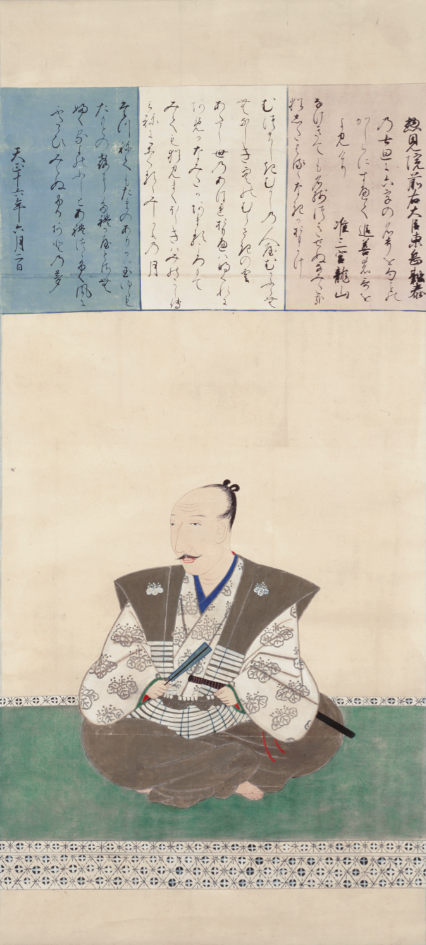

An image of Oda Nobunaga (Copy)

Copyist unknown. Original by Konoe Samahisa (1536–1612)

19th century

[https://colbase.nich.go.jp/]

The bearers of the culture of this period were, of course, the samurai. The main players in this period changed rapidly from Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi(豊臣秀吉), and the Tokugawa family after Tokugawa Ieyasu(徳川家康). Art of this period was also highly used politically as a symbol of authority.

In particular, the lavish decoration of walls of castles and temples was favored, while the culture of the tea ceremony, which Sen no Rikyu(千利休) developed to a great extent, flourished beyond the bounds of status.

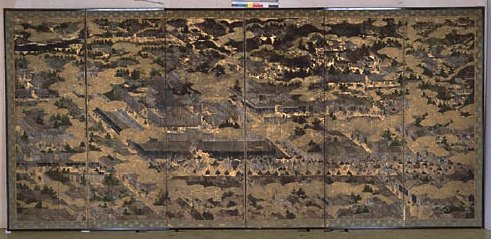

International exchange also influenced art. The arrival of Portuguese ships brought Christian culture to Japan. Trade with non-Asian countries had a great impact on tactics and religious views in addition to painting. Nanban Byobu(南蛮屏風), which feature these foreigners and foreign ships as their subjects, are art works unique to the Momoyama period.

Nanban folding screen(南蛮屏風)17th century [https://colbase.nich.go.jp/]

The Rise of the Kano School

Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi built castles, temples, and other large-scale structures. The painters of the Kano school(狩野派) responded to the demand for barrier paintings to decorate the interior spaces of these buildings.

The painters of the Kano school were responsible for many of the paintings that decorated the interior spaces of these buildings, even after the Momoyama period. Kano Eitoku(狩野永徳) was a central figure in this movement. His specialty, vivid colors and powerful depictions on gold backgrounds, were especially favored by samurai warriors, leading him to establish an absolute position as a “shogunate painter” during the Edo period (1603-1867).

The huge folding screens of “The Lions” (Karajishi-zu byobu/ 16th century) by Kano Eitoku and Kano Tsunenobu (National Treasure) [https://colbase.nich.go.jp/]

He is also famous for his paintings depicting the customs of Kyoto in and around Rakuchu-Rakugai(洛中洛外図). This folding screen painting depicts a bird’s-eye view of the city of Kyoto and depicts the customs and manners of the people of Kyoto in great detail. Many painters worked on these screens, but Kano Eitoku’s is the most well-known.

Art historian Tsuji Tadao calls this period the “Age of Kazari (decoration)”. He says, “It was a landmark period in history, marking the transition from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern period. Art was used to its fullest extent as a tool for adorning their power, and a world of “Kazari(decoration)” emerged that was full of vigor, vitality, and illusion. The background was the unprecedented gold and silver rush of the period.”

Rakuchu Rakugai zu (洛中洛外図(二条城) / Scenes in and around the Capital (Nijo Castle)

[https://colbase.nich.go.jp/]

Wabicha Designs and Political Utensils

On the other hand, another major characteristic of Momoyama art was the deepening of the wabi aesthetic, which valued the beauty of imperfection and lack of decoration, through the medium of Chanoyu (tea ceremony).

Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) promoted this culture. He was from the common class in Sakai, Osaka, and became familiar with Zen and was recognized as a tea master at a young age. As the tea master of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, he was in charge of tea ceremonies under the Emperor, but he rejected the previous opulent tea culture and created the “wabi tea room,” in which the necessary elements were reduced to the bare minimum.

a traditional tea room (茶室) photo by Tomoro Ando

The design of the tea room, which had a doorway that opened into the living room of a farmer or fisherman, reflects Rikyu’s ascetic spirit of seeking a “direct communication between the master and guest” in the tea room.

He ordered the potter Chojiro to create “Raku tea bowls,” his favorite, and the relaxing shape and feel of the Kuro-ragaku and Akaraku tea bowls with inscriptions such as “Oguro,” “Shunkan,” and “Muichi-mono” show a typical example of how Japanese art should be directly connected to daily life.

Raku tea bowls were originated by Chojiro, who was inspired by the tea master Sen no Rikyu. The bowls are shaped by hand without using a potter’s wheel, and are then shaved with a spatula. The black glaze is completely covered up to the base of the vessel, and the tranquil appearance of the vessel reflects the spirit of the times, which demanded a sense of dignity and serenity. Kuro-Raku tea bowl ”The Old Tale”(黒楽茶碗 銘むかし咄)(/16th century/from Colbase[https://colbase.nich.go.jp/]))

Tea bowls and other tea ceremony utensils were considered rewards for warriors who had distinguished themselves in battle, and a single small bowl became as valuable as a vast territory. By rewarding warriors with such works of art, Oda Nobunaga and other powerful rulers were able to control their warlords within their limited territory and achieve unification of the country.

In other words, works of art during this Sengoku period became increasingly meaningful as political tools. Due to destruction caused by warfare and changes in power, only a few Momoyama art relics remain. However, each of these artifacts radiates a unique brilliance that cannot be found in any other period.

See also The Secret of Japanese Ceramics: What makes them so original?

a traditional tea room (茶室) photo by Tomoro Ando

Some Images are from https://colbase.nich.go.jp/