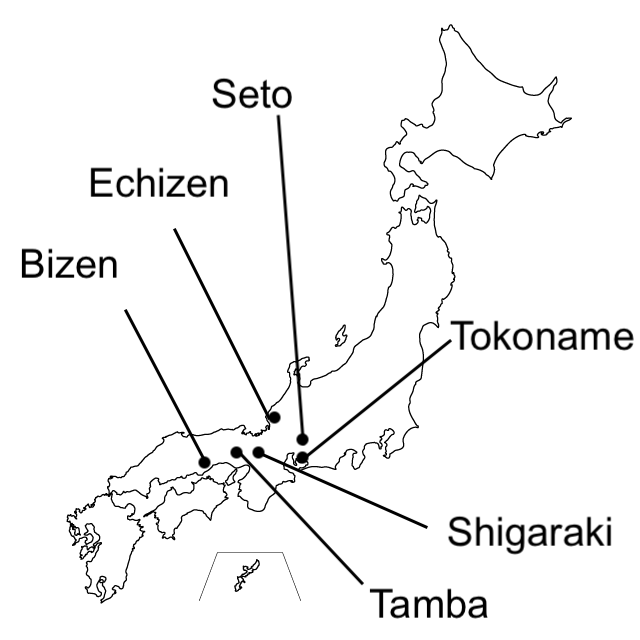

Six major ceramic areas in Japan where firing flourished during the Middle Ages. Seto (瀬戸), Tokoname (常滑), Echizen (越前), Bizen (備前), Shigaraki (信楽) and Tanba (丹波).

Although there were other production kilns, these six kilns are the only ones that have continued production activities up to the present day.

Seto Koyo (瀬戸古窯)

This is a kiln site including about 500 old kiln sites distributed in the area centering on Seto (瀬戸) City, Aichi Prefecture. There are ancient porcelain kilns, Seyuto-gama (施釉陶窯 : medieval glazed pottery kilns), Yamadyawan-gama (山茶碗窯 : unglazed pottery kilns), Ogama ( 大窯 : large kilns) from the early modern period (16th century), and renbo-shiki noborigama ( 連房式登窯 : climbing kilns) from the 17th to 19th centuries.

In 1807, Kato Tamikichi (加藤民吉) returned to Seto from Kyushu, where he had mastered the porcelain manufacturing process, and since then, production has greatly developed. He sold large quantities of high-quality dyed porcelain domestically, and Seto-mono (瀬戸物) became synonymous with ceramics and porcelain.

Tokoname Koyo (常滑古窯)

The Chita (知多) Peninsula of Aichi Prefecture has been the site of pottery production since the Middle Ages. There are more than 1,000 kiln sites throughout the peninsula. In the Heian and Kamakura periods, there are many powerful, naturally glazed jars and wares in Kotokoname (古常滑).

The shapes of these vessels include Ogame (大甕), Kyoduka-tsubo (経塚壺), Ohirabati (大平鉢), Misuji-tsubo (三筋壺), Tyomonko (刻文壺), Jiin-kawara (寺院瓦), and Gyochin (魚沈). In the Muromachi period, the ana-gama (穴窯) was replaced by the teppo-gama (鉄砲窯), and black-brown pots called mayake (真焼) were actively fired. These were similar to Nambanmono (南蛮物), Bizen (備前) ware, and Tamba (丹波) ware.

Since the Meiji period, the area has also been famous for its red clay teapots called Syudei-Kyusu (朱泥急須).

Echizen koyo (越前古窯)

There are more than 170 old kiln sites mainly in Ota (織田) Town and Miyazaki Village, Niu (丹生) County, Fukui Prefecture. The early ceramics of the Kamakura period are similar to those of Kotokoname, but those of the Muromachi period can be distinguished by their distinctive seals and inscriptions.

From Muromachi to the Edo period, many ohaguro (お歯黒) pots were made. Some people call the early modern pottery ‘Ota-yaki (織田焼)’.

Bizen koyo (備前古窯)

Bizen (備前) Pottery is also called Inbe (伊部) Pottery, and is produced in the area around Inbe (伊部), Bizen (備前) Town, Wake (和気) County, Okayama Prefecture. There are kiln sites near Miwa (美和) and Tamatsu (玉津) where Sue (須恵) ware is thought to have been produced since the Kofun period, and Bizen ware is said to have originated in the Nara period.

The so-called intermediate earthenware was produced from the Nara to mid-Heian periods, and has a grayish-white color, unlike the blackish base unique to Bizen.

After the Heian period, Bizen pottery began to have a distinctive iron-rich surface.

In the late Muromachi period, in addition to daily necessities such as jars, pots, and suribachi (擂鉢 : mortars), many tea ceremony utensils such as Suiji (水指) and Hanaike (花生) were produced, reaching their peak in the Momoyama period.

In general, Bizen ware is attractive for its skin variations such as hidasuki (火欅), enokihada (榎肌), goma (胡麻), shiso (紫蘇), and hima (火間).

Shigaraki koyo (信楽古窯)

The Shigaraki (信楽) area in Shiga Prefecture has more than 200 kiln sites, dating from the Middle Ages to the present day. The kilns are said to have opened at the end of the Heian period, and pots, jars, and suribachi were fired under the influence of Tokoname ware.

The seed pots and other miscellaneous daily utensils found at the kiln site are said to be relics from the end of the Kamakura period to the early Muromachi period.

The clay containing Tyosekiryu (長石粒) is of high quality and is highly valued for its rich natural glaze and rich scenery of Shigaraki in the Middle Ages.

In the late Muromachi period, tea ceremony utensils attracted attention, and tea ceremony utensils dominated the Momoyama period. Around the Bunka-Bunsei period, mass production of miscellaneous daily-use wares began to be noticed.

Compared to Tokoname, Echizen, and Tamba (丹波), Shigaraki clay is low in iron content and generally has a light coloring.

Tanba koyo (丹波古窯)

Tanba koyo (丹波古窯), located mainly in Konda-cho (今日町), Taki (多紀) gun, Hyogo Prefecture, have been in existence from the Middle Ages to the present day in kilns such as Kamitachikui (上立杭), Shimotachikui Kamaya (下立杭釜屋), Onobara (小野原), and others. Tachikui (立杭) is still known today as a private kiln. Most of the jars and pots handed down from generation to generation are from the Muromachi period or later, and those fired after the Kanei period according to the taste of Kobori Enshu (小堀遠州) are called Enshu Tamba (遠州丹波).

The base material of kotanba (古丹波) is unglazed and some are naturally glazed, and in the 15th century, jars with a heavy feel with a glowing brown burnished skin were fired.

Some Tamba ware is similar to Koseto (古瀬戸) and Karatsu (唐津) glaze, while others are similar to Yucho (釉調), Sakuyuki (作行), and Zeze (膳所) ware.

See also The Secret of Japanese Ceramics: What makes them so original?