In Denmark – like the rest of Europe – Japanese art is most often associated with Hokusai’s woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa (c. 1831). As a collector of Japanese prints, my interest also began with the classic ukiyo-e. But it was while researching Danish late 19th-century porcelain during my Art History studies, that I realised the significant role that the Japanese prints played in influencing Danish design in particular.

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, woodblock print, c. 1831. @Metropolitan Museum of Art.

See also Who is Katsushika Hokusai? What is so great about ‘Great Wave’?

With the opening of Japan’s ports in the mid-1850s, a stream of objects such as porcelain, lacquerware, bronzes, textiles as well as woodblock prints and books were exported to the big European and North American cities, with Paris as the epicentre, fuelling a craze for everything Japanese. A phenomenon that was to be defined by the French art critic and collector Phillipe Burty in 1872 as Japonisme.

The Japanese woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, came to inspire a whole generation of Western artists and designers, and the Danes also got caught in the wave of excitement and fascination for the ‘exotic’ art of Japan, and in particular the colourful ukiyo-e.

In Denmark, painter and art historian Karl Madsen wrote the first book, Japansk Malerkunst (Japanese Painting), in a Scandinavian language about Japanese art, published in 1885. This became an important source of knowledge and inspiration for Scandinavian artists, with an entire chapter dedicated solely to Hokusai.

Karl Madsen, Japansk Malerkunst, P.G. Philipsens Forlag, Copenhagen, 1885.

Around the same time, a young architect, Emil Arnold Krog (1856-1931), was brought to the Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Manufactory (today Royal Copenhagen) to help promote a modern ‘national’ style. Inspired by the earlier blue fluted porcelain service and to a large degree by the Japanese artistic depictions of nature that he saw in netsuke and ukiyo-e – Krog created porcelain works with the distinctive blue underglaze that were Nordic in feeling but with a clear Japanese touch.

Emil Arnold Krog, porcelain dish with swans and waves, blue underglaze, 1887. @Designmuseum Denmark. Photo by Pernille Klemp.

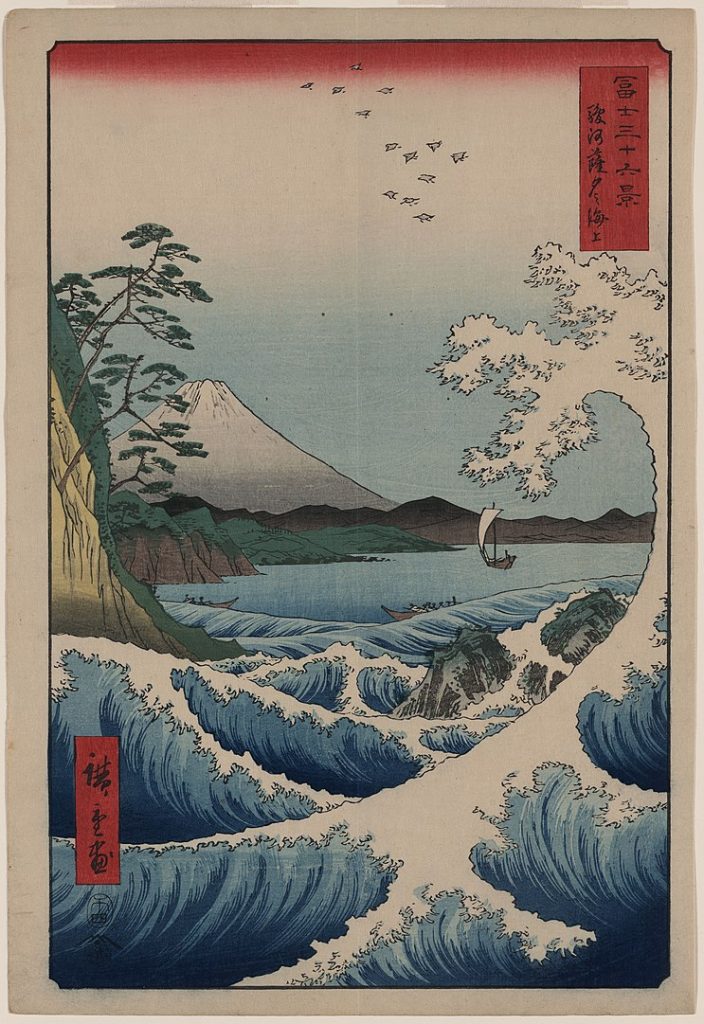

A dish from 1888 with swans flying over a stormy sea shows the inspiration from the famous wave motifs by Katsushika Hokusai as well Utagawa Hiroshige collected by many Western artists at the time, such as “The Sea off Satta” from 1858.

Utagawa Hiroshige, The Sea at Satta, woodblock print, 1858.

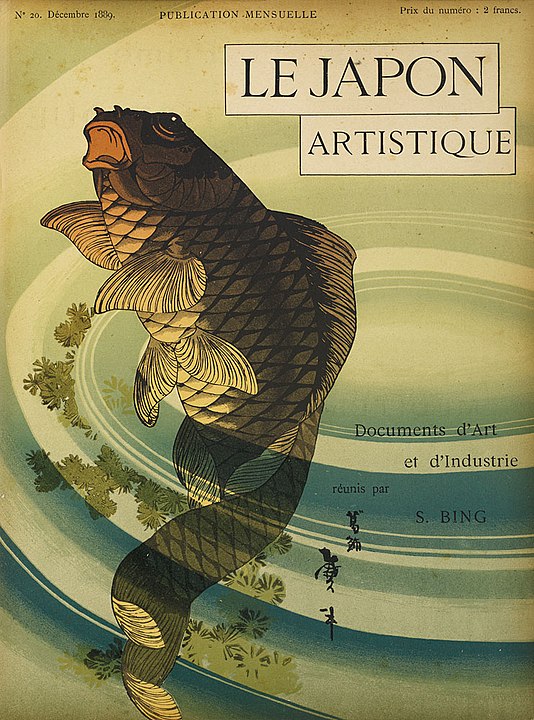

Although it is not known exactly which Japanese prints Arnold Krog collected himself, we know that he had access to the influential French magazine Le Japon Artistique, published by Siegfried Bing in Paris in 1888-91, in which many famous Japanese works of art were reproduced, and always had a motif from a known ukiyo-e on the cover.

S. Bing (ed.), Le Japon Artistique, No. 20, December, 1889.

Today, the influence from Japan still shines through in Danish design and architecture. But there are not many collections in Denmark of Japanese art – including ukiyo-e –, a surprising fact considering the important role that Japanese aesthetics have played since the late 19th century.

Back in 1974, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark held a major Japan-exhibition and invited contemporary Japanese artists to participate with works, displayed alongside a selection of classic Japanese art, including ukiyo-e by Hokusai, Utamaro and others.

Ay-O, Exhibition Poster for Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, detail from Hokusai Rainbow, 1974. Collection of Malene Wagner.

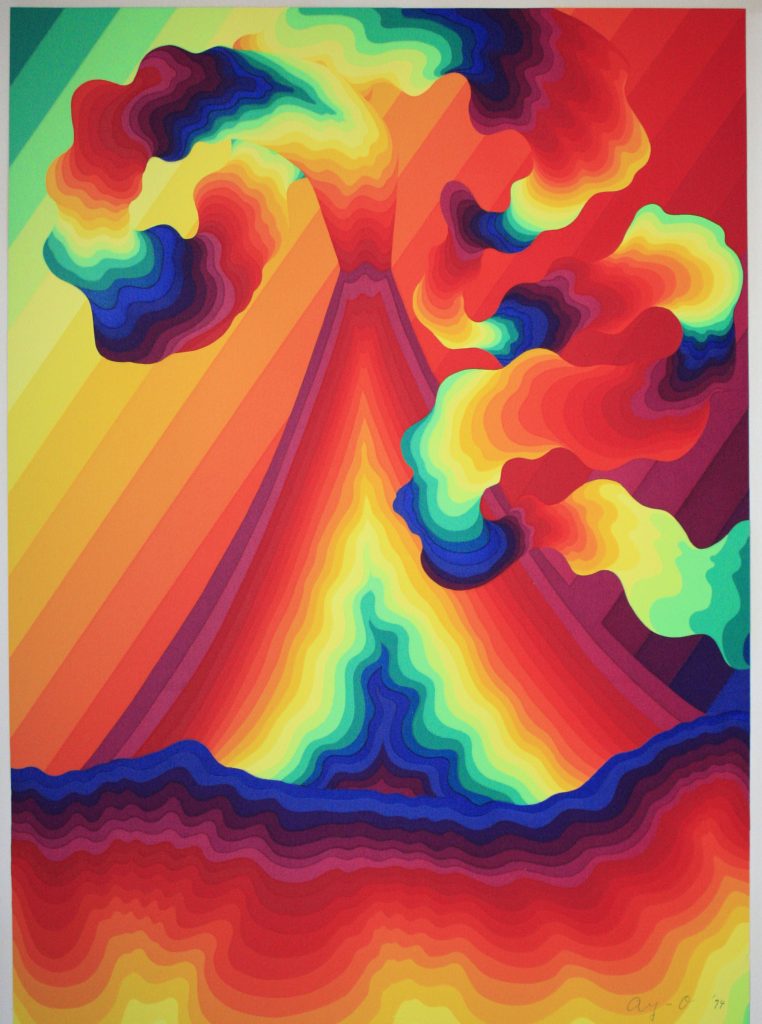

Among the invited contemporary artists was Ay-O (靉嘔/born Iijima Takao in 1931), also known as the “rainbow artist”, who was commissioned to create five silkscreen prints for the show. The series was titled Rainbow Landscape.

Ay-O, Vulcano, silkscreen print, 1974. Collection of Malene Wagner.

This was one of the first prints that I bought for my collection many years later. It was sold at a Danish auction as a poster.

I met Ay-O in the autumn of 2019 and again in 2022, when I had the honour of interviewing him for a book on modern Japanese prints that I am working on. Ay-O stands out among the modern Japanese print artists, as he worked in many different media, but his works play an important part in the history of the Japanese print.

Ay-O and Malene, October 2022. Photo by Ando Tomoro.

Ay-O, who moved to New York in 1958, was part of the avant-garde Fluxus Movement, which also included members such as George Maciunas (the founder), Nam June Paik as well as Danish artist Eric Andersen.

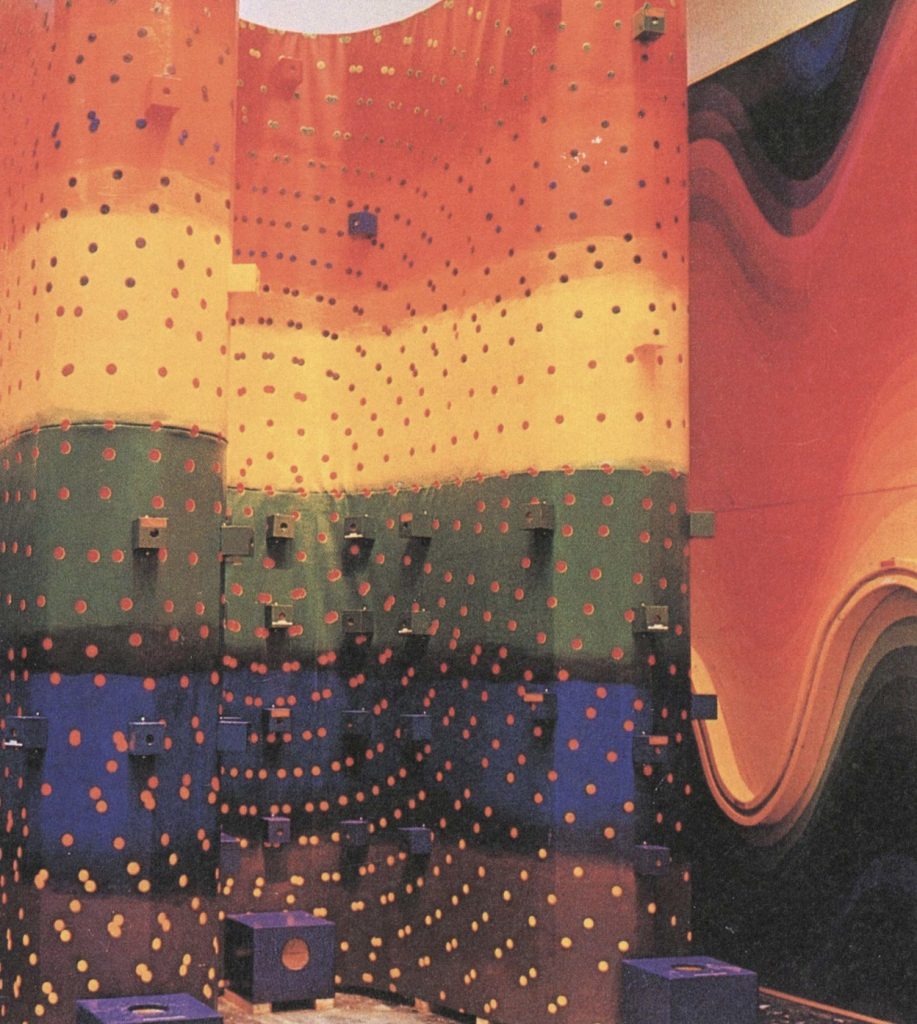

In 1966, Ay-O represented Japan at the 33rd Venice Biennale with his Rainbow Environment 3, which included a wall of 65 rainbow-coloured ‘finger boxes’ with holes in which the visitors were invited to explore its’ contents.

Ay-O, Rainbow Environment No. 3, Venice Biennale, 1966. @ The Japan Foundation.

That was the same year that his contemporary Kusama Yayoi (b. 1929) participated with her art installation Narcissus Garden without an official invite (she was later asked to leave the biennale). Today, Kusama is considered one of the most famous and highest-valued Japanese artists. Her prints fetch prices up in the ten-thousands of USD, whereas Ay-O’s works can be found for a few hundred USD. An interesting change from the 60s to today.

Kusama’s dots have become iconic, just like Hokusai’s Great Wave, which in its time would have been sold for around the same price as a double serving of rice, and in 2021 broke sale record with a hammer price of 1.59 mio USD.

But one thing is monetary value, another is aesthetic and cultural value, and that is why it is important that the continuing history and development of Japanese prints is being told – both in Japan and abroad. With many talented print artists graduating from Japanese schools and universities, it is important that we present and promote the new generation of artists to continue the history beyond The Great Wave.

(This article is a reprint from a content of Waraku web with the great cooperation of the website.)