Kutaniyaki is a type of ceramics produced in southern Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. This pottery is known for its beautiful overglaze enameled decoration and picturesque designs such as flowers and birds. This post describes the history and characteristics of Kutaniyaki, which attracts people not only from Japan but also from all over the world.

Mysterious and Vanished Kiln

Kutani-yaki is a traditional Japanese ceramic ware with a history dating back more than 400 years. It dates back to the early Edo period (1655), when pottery stones were discovered in Kutani Village (now Yamanaka Onsen Kutani-machi, Kaga City), deep in the mountains of the Daishoji Domain, a branch of the Kaga Domain, and Toshiharu Maeda, the first Daishoji Domain lord, introduced Arita pottery-making techniques and built a kiln in Kutani Village.

Old Climbing Kiln of Kutani. Used in 1940-1965.

The works from this period are known as ‘kokutani’ (old Kutani) and are considered masterpieces of Japanese coloured porcelain, but only 50 years after their birth they suddenly ceased to be made.There are various theories as to why, including the death of Toshiharu, the financial difficulties of the clan and interference by the Tokugawa Shogunate, but it is still unclear.

In the late Edo period, porcelain production resumes in the Kaga and Daishoji clans. In 1824 (Bunsei 7), Yoshidaya Den-emon, a wealthy merchant from the Daishoji clan, opened a kiln in Kutani Village with a huge private fortune.

A koro(香炉)of Kutani ware. it is used for burning an incense.

The works of the Yoshidaya kilns, which mainly focused on reviving Old Kutani, were at that time the only type of Kutani ware known as ‘Kutani-yaki’, a name used until before the Meiji era only for the works of the Yoshidaya kilns and their successors in the Daishoji domain, as well as some kilns influenced by the Yoshidaya kilns.

After the Meiji Restoration, the pottery makers who lost the clan’s support were forced to fend for themselves, and the production areas of Kanazawa, Nohmi (only) and Komatsu produced large quantities of work under the name ‘Japan Kutani’ and sought opportunities in the export industry. Meanwhile, in the Kaga area, which had its origins in the Daishoji clan, the quality of the work was further improved under the creed of ‘ippin seisaku’ (one-piece production).

The tradition of producing handmade quality products, which has been handed down from Ko-Kutani, has been carefully passed down together with the climbing kilns built by Den-emon in the area, and is still alive today as the tradition of Kutani-yaki in Kaga.

A tool of painting Kutani ware. Putting a pot on here and paint it with brush.

Unique style incorporating Japanese painting

Kutani Yaki ceramics are covered with a beautiful glaze. Glazes are used to protect the surface of dishes and vases and enrich their colours, and Kutani Yaki uses many unique glazes, allowing the wearer to enjoy a variety of colours such as blue, green, brown and purple.

Iro-e in Kutani Yaki refers to ‘Gosai-te’, which uses five colours (green, yellow, purple, dark blue and red). It is a gorgeous style in which motifs such as Chinese-style landscapes, figures, flowers, birds, wind and moon are painted in a pictorial manner, making use of the margins in the centre of the vessel. The Ko-Kutani style was not limited to following the Chinese style, but was perfected as a unique style, incorporating the compositions of Japanese painting.

An old Kutani ware

Aote” is a representative style of Ko-Kutani, the origin of Kutani-yaki. The bold design, in which the entire vessel is heavily painted in four colours (green, yellow, dark blue and purple) without the use of red, is unique among Japanese coloured porcelain. The Yoshidaya kiln, which revived Kutani ware in the late Edo period and opened a kiln in the area, specialised in aote, which is reminiscent of Ko-Kutani ware. Ko-Kutani ware is described as being full of grandeur reminiscent of samurai warriors, while Yoshidaya ware is more civilised and graceful.

Rosanjin’s pottery master, Suda Seika

Suda Seika I, a well-known Kutani-yaki potter, was one of the most important ceramic artists who greatly influenced the world of Kutani-yaki with his unique style and artistic approach.

One of a works of Suda Seika I (the first).

Suda worked as a young man in Tokyo copying old paintings, and after graduating from the pottery department of the Ishikawa prefectural government in 1880 (Meiji 13), he went on to study pottery making in Kyoto. He then joined the Kutani Pottery Company, where he worked as head painter. After the company was dissolved in 1891, Jinghua set up his own business, Jinghua Kiln in Kaga City, where he produced a wide range of old works in a variety of styles, including somezuki, kosu-akae, koakae and kokutani.

His works are also characterised by their sumptuous decoration using gold leaf, known as kinsai, and the technique of kinsai is extremely elaborate and unique.

One of the works of Suda Seika I.

In 1915, Kitaoji Rosanjin visited the pottery and was taught by Jinghua I, which is said to have opened his eyes to the charms of pottery making. Rosanjin, who at the time was a calligrapher by the name of Fukuda Taikan, was invited as a guest of the owner of the former Yoshinoya Ryokan in Yamashiro Onsen by the Kanazawa-based Chinese scholar Hosono Endai, and carved signs for the ryokan and other inns. The signboards became a connection, and Rosanjin took his first steps as a ceramic artist under the tutelage of Suda Jinghua, the first generation of the Suda family.

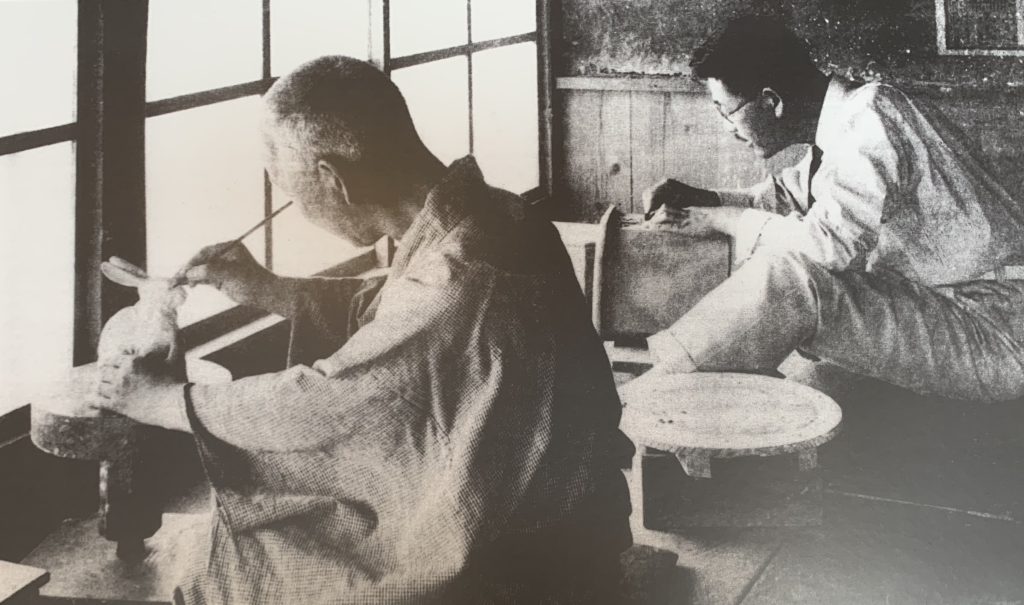

Suda Seika I (left) and Kitaoji Rosanjin (right). 1924 c.a.

In the late Taisho period (1912-1926), Rosanjin opened his own exclusive members-only restaurant, Hoshioka Saryo, in Akasaka, Tokyo, and continued to visit Yamashiro frequently to make pottery. In his later years, even after he had made a name for himself as a potter and chef, he was always fond of his villa in Yamashiro.

The Secret of Japanese Ceramics: What makes them so original?